Buoyant force is greatest on a submerged A) 1-cubic centimeter block of lead. B) 1-cubic centimeter block of aluminum. C) is the same on each. Buoyant force is equal to the weight of the water displaced. The weight of the water displaced has nothing to do with the weight of the object (10N), it has to do with the volume of the object. (5 votes) See 1 more reply. Buoyant force is greatest on a submerged. A) is the same on each. B) 1-cubic centimeter block of lead. C) 1-cubic centimeter block of alumin. B) smaller diameter piston. To multiply the input force of a hydraulic lift, the input end should be the one having the. A) Relative piston sizes don't matter.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define buoyant force

- State Archimedes’ principle

- Describe the relationship between density and Archimedes’ principle

When placed in a fluid, some objects float due to a buoyant force. Where does this buoyant force come from? Why is it that some things float and others do not? Do objects that sink get any support at all from the fluid? Is your body buoyed by the atmosphere, or are only helium balloons affected ((Figure))?

Figure 14.19 (a) Even objects that sink, like this anchor, are partly supported by water when submerged. (b) Submarines have adjustable density (ballast tanks) so that they may float or sink as desired. (c) Helium-filled balloons tug upward on their strings, demonstrating air’s buoyant effect. (credit b: modification of work by Allied Navy; credit c: modification of work by “Crystl”/Flickr)

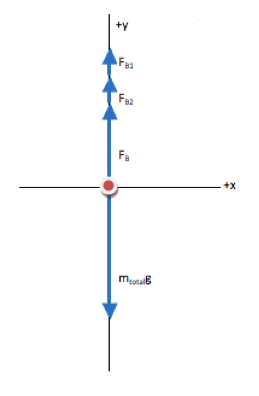

Answers to all these questions, and many others, are based on the fact that pressure increases with depth in a fluid. This means that the upward force on the bottom of an object in a fluid is greater than the downward force on top of the object. There is an upward force, or buoyant force, on any object in any fluid ((Figure)). If the buoyant force is greater than the object’s weight, the object rises to the surface and floats. If the buoyant force is less than the object’s weight, the object sinks. If the buoyant force equals the object’s weight, the object can remain suspended at its present depth. The buoyant force is always present, whether the object floats, sinks, or is suspended in a fluid.

Buoyant Force

The buoyant force is the upward force on any object in any fluid.

Figure 14.20 Pressure due to the weight of a fluid increases with depth because [latex] p=hpg [/latex]. This change in pressure and associated upward force on the bottom of the cylinder are greater than the downward force on the top of the cylinder. The differences in the force results in the buoyant force [latex] {F}_{text{B}} [/latex]. (Horizontal forces cancel.)

Archimedes’ Principle

Just how large a force is buoyant force? To answer this question, think about what happens when a submerged object is removed from a fluid, as in (Figure). If the object were not in the fluid, the space the object occupied would be filled by fluid having a weight [latex] {w}_{text{fl}}. [/latex] This weight is supported by the surrounding fluid, so the buoyant force must equal [latex] {w}_{text{fl}}, [/latex] the weight of the fluid displaced by the object.

The buoyant force on an object equals the weight of the fluid it displaces. Patch traktor pro 3. In equation form, Archimedes’ principle is

where [latex] {F}_{text{B}} [/latex] is the buoyant force and [latex] {w}_{text{fl}} [/latex] is the weight of the fluid displaced by the object.

This principle is named after the Greek mathematician and inventor Archimedes (ca. 287–212 BCE), who stated this principle long before concepts of force were well established.

Figure 14.21 (a) An object submerged in a fluid experiences a buoyant force [latex] {F}_{text{B}}. [/latex] If [latex] {F}_{text{B}} [/latex] is greater than the weight of the object, the object rises. If [latex] {F}_{text{B}} [/latex] is less than the weight of the object, the object sinks. (b) If the object is removed, it is replaced by fluid having weight [latex] {w}_{text{fl}}. [/latex] Since this weight is supported by surrounding fluid, the buoyant force must equal the weight of the fluid displaced.

Archimedes’ principle refers to the force of buoyancy that results when a body is submerged in a fluid, whether partially or wholly. The force that provides the pressure of a fluid acts on a body perpendicular to the surface of the body. In other words, the force due to the pressure at the bottom is pointed up, while at the top, the force due to the pressure is pointed down; the forces due to the pressures at the sides are pointing into the body.

Since the bottom of the body is at a greater depth than the top of the body, the pressure at the lower part of the body is higher than the pressure at the upper part, as shown in (Figure). Therefore a net upward force acts on the body. This upward force is the force of buoyancy, or simply buoyancy.

Density and Archimedes’ Principle

If you drop a lump of clay in water, it will sink. But if you mold the same lump of clay into the shape of a boat, it will float. Because of its shape, the clay boat displaces more water than the lump and experiences a greater buoyant force, even though its mass is the same. The same is true of steel ships.

The average density of an object is what ultimately determines whether it floats. If an object’s average density is less than that of the surrounding fluid, it will float. The reason is that the fluid, having a higher density, contains more mass and hence more weight in the same volume. The buoyant force, which equals the weight of the fluid displaced, is thus greater than the weight of the object. Likewise, an object denser than the fluid will sink.

The extent to which a floating object is submerged depends on how the object’s density compares to the density of the fluid. In (Figure), for example, the unloaded ship has a lower density and less of it is submerged compared with the same ship when loaded. We can derive a quantitative expression for the fraction submerged by considering density. The fraction submerged is the ratio of the volume submerged to the volume of the object, or

The volume submerged equals the volume of fluid displaced, which we call [latex] {V}_{fl} [/latex]. Now we can obtain the relationship between the densities by substituting [latex] rho =frac{m}{V} [/latex] into the expression. This gives

where [latex] {rho }_{text{obj}} [/latex] is the average density of the object and [latex] {rho }_{text{fl}} [/latex] is the density of the fluid. Since the object floats, its mass and that of the displaced fluid are equal, so they cancel from the equation, leaving

We can use this relationship to measure densities.

Figure 14.22 An unloaded ship (a) floats higher in the water than a loaded ship (b).

Example

Calculating Average Density

Buoyant Force Is Greatest On A Submerged Object

Suppose a 60.0-kg woman floats in fresh water with 97.0% of her volume submerged when her lungs are full of air. What is her average density?

Strategy

We can find the woman’s density by solving the equation

for the density of the object. This yields

We know both the fraction submerged and the density of water, so we can calculate the woman’s density.

Solution

Entering the known values into the expression for her density, we obtain

Significance

The woman’s density is less than the fluid density. We expect this because she floats.

Numerous lower-density objects or substances float in higher-density fluids: oil on water, a hot-air balloon in the atmosphere, a bit of cork in wine, an iceberg in salt water, and hot wax in a “lava lamp,” to name a few. A less obvious example is mountain ranges floating on the higher-density crust and mantle beneath them. Even seemingly solid Earth has fluid characteristics.

Measuring Density

One of the most common techniques for determining density is shown in (Figure).

Figure 14.23 (a) A coin is weighed in air. (b) The apparent weight of the coin is determined while it is completely submerged in a fluid of known density. These two measurements are used to calculate the density of the coin.

An object, here a coin, is weighed in air and then weighed again while submerged in a liquid. The density of the coin, an indication of its authenticity, can be calculated if the fluid density is known. We can use this same technique to determine the density of the fluid if the density of the coin is known.

All of these calculations are based on Archimedes’ principle, which states that the buoyant force on the object equals the weight of the fluid displaced. This, in turn, means that the object appears to weigh less when submerged; we call this measurement the object’s apparent weight. The object suffers an apparent weight loss equal to the weight of the fluid displaced. Alternatively, on balances that measure mass, the object suffers an apparent mass loss equal to the mass of fluid displaced. That is, apparent weight loss equals weight of fluid displaced, or apparent mass loss equals mass of fluid displaced.

Summary

- Buoyant force is the net upward force on any object in any fluid. If the buoyant force is greater than the object’s weight, the object will rise to the surface and float. If the buoyant force is less than the object’s weight, the object will sink. If the buoyant force equals the object’s weight, the object can remain suspended at its present depth. The buoyant force is always present and acting on any object immersed either partially or entirely in a fluid.

- Archimedes’ principle states that the buoyant force on an object equals the weight of the fluid it displaces.

Conceptual Questions

More force is required to pull the plug in a full bathtub than when it is empty. Does this contradict Archimedes’ principle? Explain your answer.

Show SolutionNot at all. Pascal’s principle says that the change in the pressure is exerted through the fluid. The reason that the full tub requires more force to pull the plug is because of the weight of the water above the plug.

Do fluids exert buoyant forces in a “weightless” environment, such as in the space shuttle? Explain your answer.

Will the same ship float higher in salt water than in freshwater? Explain your answer.

Show SolutionThe buoyant force is equal to the weight of the fluid displaced. The greater the density of the fluid, the less fluid that is needed to be displaced to have the weight of the object be supported and to float. Since the density of salt water is higher than that of fresh water, less salt water will be displaced, and the ship will float higher.

Marbles dropped into a partially filled bathtub sink to the bottom. Part of their weight is supported by buoyant force, yet the downward force on the bottom of the tub increases by exactly the weight of the marbles. Explain why.

Problems

What fraction of ice is submerged when it floats in freshwater, given the density of water at [latex] 0,text{°C} [/latex] is very close to [latex] 1000,{text{kg/m}}^{3} [/latex]?

If a person’s body has a density of [latex] 995,{text{kg/m}}^{3} [/latex], what fraction of the body will be submerged when floating gently in (a) freshwater? (b) In salt water with a density of [latex] 1027,{text{kg/m}}^{3} [/latex]?

A rock with a mass of 540 g in air is found to have an apparent mass of 342 g when submerged in water. (a) What mass of water is displaced? (b) What is the volume of the rock? (c) What is its average density? Is this consistent with the value for granite?

Archimedes’ principle can be used to calculate the density of a fluid as well as that of a solid. Suppose a chunk of iron with a mass of 390.0 g in air is found to have an apparent mass of 350.5 g when completely submerged in an unknown liquid. (a) What mass of fluid does the iron displace? (b) What is the volume of iron, using its density as given in (Figure)? (c) Calculate the fluid’s density and identify it.

Show Solutiona. 39.5 g; b. [latex] 50,{text{cm}}^{3} [/latex]; c. [latex] 0.79,{text{g/cm}}^{3} [/latex]; ethyl alcohol

Calculate the buoyant force on a 2.00-L helium balloon. (b) Given the mass of the rubber in the balloon is 1.50 g, what is the net vertical force on the balloon if it is let go? Neglect the volume of the rubber.

What is the density of a woman who floats in fresh water with [latex] 4.00text{%} [/latex] of her volume above the surface? (This could be measured by placing her in a tank with marks on the side to measure how much water she displaces when floating and when held under water.) (b) What percent of her volume is above the surface when she floats in seawater?

Show Solutiona. [latex] {960,text{kg/m}}^{3} [/latex]; b. 6.34%; She floats higher in seawater.

A man has a mass of 80 kg and a density of [latex] 955{text{kg/m}}^{3} [/latex] (excluding the air in his lungs). (a) Calculate his volume. (b) Find the buoyant force air exerts on him. (c) What is the ratio of the buoyant force to his weight?

A simple compass can be made by placing a small bar magnet on a cork floating in water. (a) What fraction of a plain cork will be submerged when floating in water? (b) If the cork has a mass of 10.0 g and a 20.0-g magnet is placed on it, what fraction of the cork will be submerged? (c) Will the bar magnet and cork float in ethyl alcohol?

Show Solutiona. 0.24; b. 0.68; c. Yes, the cork will float in ethyl alcohol.

What percentage of an iron anchor’s weight will be supported by buoyant force when submerged in salt water?

Referring to (Figure), prove that the buoyant force on the cylinder is equal to the weight of the fluid displaced (Archimedes’ principle). You may assume that the buoyant force is [latex] {F}_{2}-{F}_{1} [/latex] and that the ends of the cylinder have equal areas[latex] A [/latex]. Note that the volume of the cylinder (and that of the fluid it displaces) equals [latex] ({h}_{2}-{h}_{1})A [/latex].

Show Solution[latex] begin{array}{ccc}text{net},Fhfill & =hfill & {F}_{2}-{F}_{1}={p}_{2}A-{p}_{1}A=({p}_{2}-{p}_{1})A=({h}_{2}{rho }_{text{fl}}g-{h}_{1}{rho }_{text{fl}}g)Ahfill & =hfill & ({h}_{2}-{h}_{1}){rho }_{text{fl}}gA,text{where},{rho }_{text{fl}}=text{density of fluid}text{.}hfill text{net},Fhfill & =hfill & ({h}_{2}-{h}_{1})A{rho }_{text{fl}}g={V}_{text{fl}}{rho }_{text{fl}}g={m}_{text{fl}}g={w}_{text{fl}}hfill end{array} [/latex]

A 75.0-kg man floats in freshwater with 3.00% of his volume above water when his lungs are empty, and 5.00% of his volume above water when his lungs are full. Calculate the volume of air he inhales—called his lung capacity—in liters. (b) Does this lung volume seem reasonable?

Glossary

- Archimedes’ principle

- buoyant force on an object equals the weight of the fluid it displaces

- buoyant force

- net upward force on any object in any fluid due to the pressure difference at different depths

How Does The Buoyant Force On A Submerged Object

When you rise from lounging in a warm bath, your arms feel strangely heavy. This is because you no longer have the buoyant support of the water. Where does this buoyant force come from? Why is it that some things float and others do not? Do objects that sink get any support at all from the fluid? Is your body buoyed by the atmosphere, or are only helium balloons affected (Figure (PageIndex{1}))?

Answers to all these questions, and many others, are based on the fact that pressure increases with depth in a fluid. This means that the upward force on the bottom of an object in a fluid is greater than the downward force on the top of the object. There is a net upward, or buoyant force on any object in any fluid (Figure (PageIndex{2})). If the buoyant force is greater than the object’s weight, the object will rise to the surface and float. If the buoyant force is less than the object’s weight, the object will sink. If the buoyant force equals the object’s weight, the object will remain suspended at that depth. The buoyant force is always present whether the object floats, sinks, or is suspended in a fluid.

Defintion: Buoyant Force

The buoyant force is the net upward force on any object in any fluid.

Just how great is this buoyant force? To answer this question, think about what happens when a submerged object is removed from a fluid, as in Figure (PageIndex{3}).

The space it occupied is filled by fluid having a weight (w_{fl}). This weight is supported by the surrounding fluid, and so the buoyant force must equal (w_{fl}), the weight of the fluid displaced by the object. It is a tribute to the genius of the Greek mathematician and inventor Archimedes (ca. 287–212 B.C.) that he stated this principle long before concepts of force were well established. Stated in words, Archimedes’ principle is as follows: The buoyant force on an object equals the weight of the fluid it displaces. In equation form, Archimedes’ principle is

[F_B = w_{fl},]

where (F_B) is the buoyant force and (w_{fl}) is the weight of the fluid displaced by the object. Archimedes’ principle is valid in general, for any object in any fluid, whether partially or totally submerged.

Archimedes’ Principle

According to this principle the buoyant force on an object equals the weight of the fluid it displaces. In equation form, Archimedes’ principle is [F_B = w_{fl},] where (F_B) is the buoyant force and (w_{fl}) is the weight of the fluid displaced by the object.

Humm … High-tech body swimsuits were introduced in 2008 in preparation for the Beijing Olympics. One concern (and international rule) was that these suits should not provide any buoyancy advantage. How do you think that this rule could be verified?

Making Connections: Take-Home Investigation

The density of aluminum foil is 2.7 times the density of water. Take a piece of foil, roll it up into a ball and drop it into water. Does it sink? Why or why not? Can you make it sink?

Floating and Sinking

Drop a lump of clay in water. It will sink. Then mold the lump of clay into the shape of a boat, and it will float. Because of its shape, the boat displaces more water than the lump and experiences a greater buoyant force. The same is true of steel ships.

Example (PageIndex{1}): Calculating buoyant force: dependency on shape

- Calculate the buoyant force on 10,000 metric tons ((1.00 times 10^7 , kg)) of solid steel completely submerged in water, and compare this with the steel’s weight.

- What is the maximum buoyant force that water could exert on this same steel if it were shaped into a boat that could displace (1.00 times 10^5 , m^3) of water?

Strategy for (a)

To find the buoyant force, we must find the weight of water displaced. We can do this by using the densities of water and steel given in [link]. We note that, since the steel is completely submerged, its volume and the water’s volume are the same. Once we know the volume of water, we can find its mass and weight.

Solution for (a) Microsoft word remove asian text font from styles.

First, we use the definition of density (rho = frac{m}{V}) to find the steel’s volume, and then we substitute values for mass and density. This gives

[V_{st} = dfrac{m_{st}}{rho_{st}} = dfrac{1.00 times 10^7 , kg}{7.8 times 10^3 , kg/m^3} = 1.28 times 10^3 , m^3.]

Because the steel is completely submerged, this is also the volume of water displaced, (V_W). We can now find the mass of water displaced from the relationship between its volume and density, both of which are known. This gives

[m_W = rho_WV_W = (1.000 times 10^3 , kg/m^3)(1.28 times 10^3 , m^3)]

[= 1.3 times 10^6 , kg.]

By Archimedes’ principle, the weight of water displaced is (m_Wg), so the buoyance force is

[F_B = w_W = m_Wg = (1.28 times 10^6space kg)(9.80 , m/s^2)]

[= 1.3 times 10^7 , N.]

The steel’s weight is (m_W g = 9.80 times 10^7 , N),

which is much greater than the buoyant force, so the steel will remain submerged. Note that the buoyant force is rounded to two digits because the density of steel is given to only two digits.

Strategy for (b)

Here we are given the maximum volume of water the steel boat can displace. The buoyant force is the weight of this volume of water.

Solution for (b)

The mass of water displaced is found from its relationship to density and volume, both of which are known. That is,

[m_W = rho_WV_W = (1.000 times 10^3 , kg/m^3)(1.00 times 10^5 , m^3)]

[= 9.80 times 10^8 , kg.]

The maximum buoyant force is the weight of this much water, or

[F_B = w_W = m_W g = (1.00 times 10^8 , kg)(9.80 , m/s^2)]

[= times 10^8 , N.]

Discussion

The maximum buoyant force is ten times the weight of the steel, meaning the ship can carry a load nine times its own weight without sinking.

Making Connections: Take-Home Investigation

- A piece of household aluminum foil is 0.016 mm thick. Use a piece of foil that measures 10 cm by 15 cm. (a) What is the mass of this amount of foil? (b) If the foil is folded to give it four sides, and paper clips or washers are added to this “boat,” what shape of the boat would allow it to hold the most “cargo” when placed in water? Test your prediction.

Density and Archimedes’ Principle

Density plays a crucial role in Archimedes’ principle. The average density of an object is what ultimately determines whether it floats. If its average density is less than that of the surrounding fluid, it will float. This is because the fluid, having a higher density, contains more mass and hence more weight in the same volume. The buoyant force, which equals the weight of the fluid displaced, is thus greater than the weight of the object. Likewise, an object denser than the fluid will sink.

The extent to which a floating object is submerged depends on how the object’s density is related to that of the fluid. In Figure (PageIndex{4}), for example, the unloaded ship has a lower density and less of it is submerged compared with the same ship loaded. We can derive a quantitative expression for the fraction submerged by considering density. The fraction submerged is the ratio of the volume submerged to the volume of the object, or

[fraction , submerged = dfrac{V_{sub}}{V_{obj}} = dfrac{V_{fl}}{V_{obj}}.]

The volume submerged equals the volume of fluid displaced, which we call (V_{fl}). Now we can obtain the relationship between the densities by substituting (rho = frac{m}{V}) into the expression. This gives

Java high sierra 10.13.6. [dfrac{V_{fl}}{V_{obj}} = dfrac{m_{fl}/rho_{fl}}{m_{obj}/overline{rho}_{obj}},]

where (overline{rho}_{obj}) is the average density of the object and (rho_{fl}) is the density of the fluid. Since the object floats, its mass and that of the displaced fluid are equal, and so they cancel from the equation, leaving

[fraction , submerged = dfrac{overline{rho}_{obj}}{rho_{fl}}.]

We use this last relationship to measure densities. This is done by measuring the fraction of a floating object that is submerged—for example, with a hydrometer. It is useful to define the ratio of the density of an object to a fluid (usually water) as specific gravity:

[specific , gravity = dfrac{overline{rho}}{rho_W},] where (overline{rho}) is the average density of the object or substance and (rho_W) is the density of water at 4.00°C. Specific gravity is dimensionless, independent of whatever units are used for (rho). If an object floats, its specific gravity is less than one. If it sinks, its specific gravity is greater than one. Moreover, the fraction of a floating object that is submerged equals its specific gravity. If an object’s specific gravity is exactly 1, then it will remain suspended in the fluid, neither sinking nor floating. Scuba divers try to obtain this state so that they can hover in the water. We measure the specific gravity of fluids, such as battery acid, radiator fluid, and urine, as an indicator of their condition. One device for measuring specific gravity is shown in Figure (PageIndex{5}).

Definition: Specific Gravity

Specific gravity is the ratio of the density of an object to a fluid (usually water).

Example (PageIndex{2}): Calculating Average Density: Floating Woman

Suppose a 60.0-kg woman floats in freshwater with (97.0%) of her volume submerged when her lungs are full of air. What is her average density?

Strategy

We can find the woman’s density by solving the equation

[fraction , submerged = dfrac{overline{rho}_{obj}}{rho_{fl}}]

for the density of the object. This yields

[overline{rho}_{obj} = overline{rho}_{person} = (fraction , submerged) cdot rho_{fl}.]

We know both the fraction submerged and the density of water, and so we can calculate the woman’s density.

Solution

Entering the known values into the expression for her density, we obtain

[overline{rho}_{person} = 0.970 cdot left(10^3 , dfrac{kg}{m^3}right) = 970 , dfrac{kg}{m^3}.]

Discussion

Her density is less than the fluid density. We expect this because she floats. Body density is one indicator of a person’s percent body fat, of interest in medical diagnostics and athletic training. (See Figure (PageIndex{7}))

There are many obvious examples of lower-density objects or substances floating in higher-density fluids—oil on water, a hot-air balloon, a bit of cork in wine, an iceberg, and hot wax in a “lava lamp,” to name a few. Less obvious examples include lava rising in a volcano and mountain ranges floating on the higher-density crust and mantle beneath them. Even seemingly solid Earth has fluid characteristics.

More Density Measurements

One of the most common techniques for determining density is shown in Figure (PageIndex{7}). An object, here a coin, is weighed in air and then weighed again while submerged in a liquid. The density of the coin, an indication of its authenticity, can be calculated if the fluid density is known. This same technique can also be used to determine the density of the fluid if the density of the coin is known. All of these calculations are based on Archimedes’ principle.

Archimedes’ principle states that the buoyant force on the object equals the weight of the fluid displaced. This, in turn, means that the object appears to weigh less when submerged; we call this measurement the object’s apparent weight. The object suffers an apparent weight loss equal to the weight of the fluid displaced. Alternatively, on balances that measure mass, the object suffers an apparent mass loss equal to the mass of fluid displaced. That is

[apparent , weight , loss = weight , of , fluid , displaced] or

[apparent , mass , loss = mass , of , fluid , displaced.]

The next example illustrates the use of this technique.

Example (PageIndex{3}): Calculating Density: Is the Coin Authentic?

The mass of an ancient Greek coin is determined in air to be 8.630 g. When the coin is submerged in water as shown in Figure (PageIndex{7}), its apparent mass is 7.800 g. Calculate its density, given that water has a density of (1.000 , g/m^3)

and that effects caused by the wire suspending the coin are negligible.

Strategy

To calculate the coin’s density, we need its mass (which is given) and its volume. The volume of the coin equals the volume of water displaced. The volume of water displaced (rho = frac{m}{V}) for (V).

Solution

The volume of water is (V_W = frac{m_W}{rho_W}) where (m_W) is the mass of water displaced. As noted, the mass of the water displaced equals the apparent mass loss, which is (m_W = 8.630 , g - 7.800 , g = 0.830 , g). Thus the volume of water is (V_W = frac{0.830 , g}{1.000 , g/cm^3} = 0.830 , cm^3). This is also the volume of the coin, since it is completely submerged. We can now find the density of the coin using the definition of density:

[rho_c = dfrac{m_c}{V_c} = dfrac{8.630 , g}{0.830 , cm^3} = 10.4 , g/cm^3.]

Discussion

You can see from [link] that this density is very close to that of pure silver, appropriate for this type of ancient coin. Most modern counterfeits are not pure silver.

This brings us back to Archimedes’ principle and how it came into being. As the story goes, the king of Syracuse gave Archimedes the task of determining whether the royal crown maker was supplying a crown of pure gold. The purity of gold is difficult to determine by color (it can be diluted with other metals and still look as yellow as pure gold), and other analytical techniques had not yet been conceived. Even ancient peoples, however, realized that the density of gold was greater than that of any other then-known substance. Archimedes purportedly agonized over his task and had his inspiration one day while at the public baths, pondering the support the water gave his body. He came up with his now-famous principle, saw how to apply it to determine density, and ran naked down the streets of Syracuse crying “Eureka!” (Greek for “I have found it”). Similar behavior can be observed in contemporary physicists from time to time!

PhET Explorations: Buoyancy

When will objects float and when will they sink? Learn how buoyancy works with blocks. Arrows show the applied forces, and you can modify the properties of the blocks and the fluid.

Summary

- Buoyant force is the net upward force on any object in any fluid. If the buoyant force is greater than the object’s weight, the object will rise to the surface and float. If the buoyant force is less than the object’s weight, the object will sink. If the buoyant force equals the object’s weight, the object will remain suspended at that depth. The buoyant force is always present whether the object floats, sinks, or is suspended in a fluid.

- Archimedes’ principle states that the buoyant force on an object equals the weight of the fluid it displaces.

- Specific gravity is the ratio of the density of an object to a fluid (usually water).

Glossary

- Archimedes’ principle

- the buoyant force on an object equals the weight of the fluid it displaces

- buoyant force

- the net upward force on any object in any fluid

- specific gravity

- the ratio of the density of an object to a fluid (usually water)

Contributors and Attributions

Paul Peter Urone (Professor Emeritus at California State University, Sacramento) and Roger Hinrichs (State University of New York, College at Oswego) with Contributing Authors: Kim Dirks (University of Auckland) and Manjula Sharma (University of Sydney). This work is licensed by OpenStax University Physics under a Creative Commons Attribution License (by 4.0).