Contents

A Patio

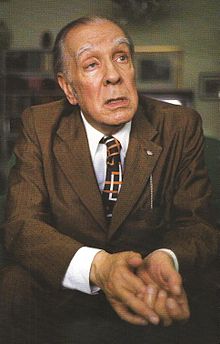

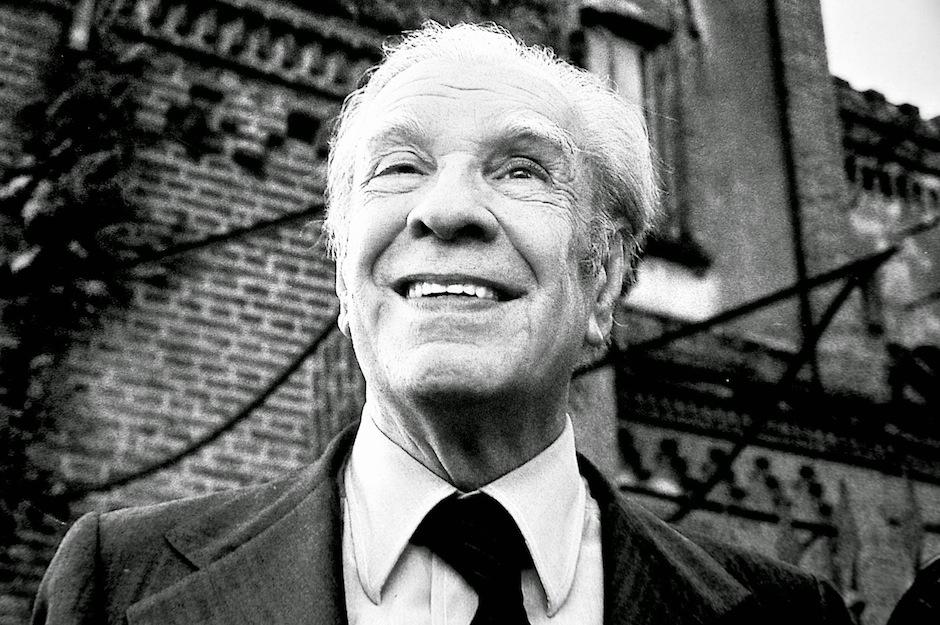

Jorge Luis Borges (24 August 1899 – 14 June 1986) was an Argentine writer who is considered one of the foremost literary figures of the 20th century. Most famous in the English speaking world for his short stories and fictive essays, Borges. Reading Jorge Luis Borges is an experience akin to having the top of one's head removed for repairs. First comes the unfamiliar breeze tickling your cerebral cortex; then disorientation, even mild discomfort; and finally, the sense that the world has been irrevocably altered-and in this case, rendered infinitely more complex. Jorge Luis Borges. The Argentine author, Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986), was one of Latin America's most original and influential prose writers and poets. His short stories revealed him as one of the great stylists of the Spanish language. Jorge Luis Borges was born on August 24, 1899, in Buenos Aires. A few years later his family moved to the.

Jorge Luis Borges. January 1, 1941. View All Credits. Jorge Luis Borges was born in Buenos Aires, in the house of his maternal grandparents, on Aug. His father, of Italian, Jewish and English heritage, professed the law but, as Mr.

At evening

they grow weary, the patio’s two or three colours.

Tonight, the moon, bright circle,

fails to dominate space.

Patio, channel of sky.

The patio is the slope

down which sky flows into the house.

Serene,

eternity waits at the crossroad of stars.

It’s pleasant to live in the friendly dark

of entrance-way, arbour, and cistern.

Simplicity

It opens, the gate to the garden

with the docility of a page

that frequent devotion questions

and inside, my gaze

has no need to fix on objects

that already exist, exact, in memory.

I know the customs and souls

and that dialect of allusions

that every human gathering goes weaving.

I’ve no need to speak

nor claim false privilege;

they know me well who surround me here,

know well my afflictions and weakness.

This is to reach the highest thing,

that Heaven perhaps will grant us:

not admiration or victory

but simply to be accepted

as part of an undeniable Reality,

like stones and trees.

Limits

Of these streets that deepen the sunset,

There must be one (but which) that I’ve walked

Already one last time, indifferently

And without knowing it, submitting

To One who sets up omnipotent laws

And a secret and a rigid measure

For the shadows, the dreams, and forms

That work the warp and weft of this life.

If all things have a limit and a value

A last time nothing more and oblivion

Who can say to whom in this house

Unknowingly, we have said goodbye?

Already through the grey glass night ebbs

And among the stack of books that throws

A broken shadow on the unlit table,

There must be one I will never read.

In the South there’s more than one worn gate

With its masonry urns and prickly pear

Where my entrance is forbidden

As it were within a lithograph.

Forever there’s a door you have closed,

And a mirror that waits for you in vain;

The crossroad seems wide open to you

And there a four-faced Janus watches.

There is, amongst your memories, one

That has now been lost irreparably;

You’ll not be seen to visit that well

Under white sun or yellow moon.

Your voice cannot recapture what the Persian

Sang in his tongue of birds and roses,

When at sunset, as the light disperses,

You long to speak imperishable things.

And the incessant Rhone and the lake,

All that yesterday on which today I lean?

They will be as lost as that Carthage

The Romans erased with fire and salt.

At dawn I seem to hear a turbulent

Murmur of multitudes who slip away;

All who have loved me and forgotten;

Space, time and Borges now leaving me.

Blake

Where will the rose in your hand exist

that lavishes, without knowing, intimate gifts?

Not in colour, because the flower is blind,

nor in the sweet inexhaustible fragrance,

nor in the weight of the petal. Those things

are sparse and remote echoes.

The real rose is more elusive.

Perhaps a pillar or a battle

or a firmament of angels, or an infinite

world, secret and necessary,

or the joy of a god we will not see

or a silver planet in another sky

or a terrible archetype lacking

the form of the rose.

A Rose and Milton

From the generations of roses

That are lost in the depths of time

I want one saved from oblivion,

One spotless rose, of all things

That ever were. Fate permits me

The gift of choosing for once

That silent flower, the last rose

That Milton held before him,

Unseen. O vermilion, or yellow

Or white rose of a ruined garden,

Your past still magically remains

Forever shines in these verses,

Gold, blood, ivory or shadow

As if in his hands, invisible rose.

Readers

Of that knight with the sallow, dry

Complexion and heroic bent, they guess

That, always on the verge of adventure,

He never sallied from his library.

The precise chronicle of his urges

And its tragic-comical reverses

Was dreamed by him, not by Cervantes,

It’s no more than a chronicle of dream.

Such my fate too. I know there’s something

Immortal and essential that I’ve buried

Somewhere in that library of the past

In which I read the history of the knight.

The slow leaves recall a child who gravely

Dreams vague things he cannot understand.

A Milonga for Manuel Flores

Manuel Flores is going to die,

That’s ‘on the money’;

Dying is a habit

That’s well-known to many.

Even so it grieves me

To say adiós to being,

That thing so familiar,

So sweet and enduring.

At dawn I gaze at my hands,

In my hands the veins there;

I gaze but don’t understand

It’s as if they were strangers.

Tomorrow four bullets will come

And oblivion with those four;

Thus said the wise Merlin:

To die is to have been born.

So many things on the road

These two eyes have seen!

When Christ has judged me

Who knows what they’ll see.

Manuel Flores is going to die,

That’s ‘on the money’;

Dying is a habit

That’s well-known to many.

New England 1967

The forms in my dreams have changed;

now there are red houses side by side

and the delicate bronze of the leaves

and chaste winter and pious wood.

As on the seventh day, the world

is good. In the twilight there persists

what’s almost non-existent, bold, sad,

an ancient murmur of Bibles, war.

Soon (they say) the first snow will fall

America waits for me on every street,

but I feel in the decline of evening

today so long, and yesterday so brief.

Buenos Aires, I go journeying

your streets, without time or reason.

The Suicide

Not a star will remain in the night.

The night itself will not remain.

I will die and with me the sum

Of the intolerable universe.

I’ll erase the pyramids, the coins,

The continents and all the faces.

I’ll erase the accumulated past.

I’ll make dust of history, dust of dust.

Now I gaze at the last sunset.

I am listening to the last bird.

I bequeath nothingness to no-one.

Things

My walking-stick, small change, key-ring,

The docile lock and the belated

Notes my few days left will grant

No time to read, the cards, the table,

A book, in its pages, that pressed

Violet, the leavings of an afternoon

Doubtless unforgettable, forgotten,

The reddened mirror facing to the west

Where burns illusory dawn. Many things,

Files, sills, atlases, wine-glasses, nails,

Which serve us, like unspeaking slaves,

So blind and so mysteriously secret!

They’ll long outlast our oblivion;

And never know that we are gone.

To the Nightingale

On what secret night in England

Or by the incalculable constant Rhine,

Lost among all the nights of my nights,

Carried to my unknowing ear

Your voice, burdened with mythology,

Nightingale of Virgil, of the Persians?

Perhaps I never heard you, yet my life

I bound to your life, inseparably.

A wandering spirit is your symbol

In a book of enigmas. El Marino

Named you the siren of the woods

And you sing through Juliet’s night

And in the intricate Latin pages

And from the pine-trees of that other,

Nightingale of Germany and Judea,

Heine, mocking, burning, mourning.

Keats heard you for all, everywhere.

There’s not one of the bright names

The people of the earth have given you

That does not yearn to match your music,

Nightingale of shadows. The Muslim

Dreamed you drunk with ecstasy

His breast trans-pierced by the thorn

Of the sung rose that you redden

With your last blood. Assiduously

I plot these lines in twilight emptiness,

Nightingale of the shores and seas,

Who in exaltation, memory and fable

Burn with love and die melodiously.

The Moon

There is such solitude in that gold.

The moon of these nights is not the moon

The first Adam saw. Long centuries

Of human vigil have filled her with

An old lament. See. She is your mirror.

Remorse

I have committed the worst of sins

One can commit. I have not been

Happy. Let the glaciers of oblivion

Take and engulf me, mercilessly.

My parents bore me for the risky

And the beautiful game of life,

For earth, water, air and fire.

I failed them, I was not happy.

Their youthful hope for me unfulfilled.

I applied my mind to the symmetric

Arguments of art, its web of trivia.

They willed me bravery. I was not brave.

It never leaves me. Always at my side,

That shadow of a melancholy man.

Alhambra

Welcome, the water’s voice

To one whom black sand overwhelmed,

Welcome, to the curved hand

The smooth column of the marble,

Welcome, slender labyrinths of water

Between the lemon trees,

Welcome the melodious zéjel,

Welcome is love, welcome the prayer

Offered to a God who is One,

Welcome the jasmine.

Vain the scimitar

Against the long lances of the host,

Vain to be the best.

Good to know, foreknow, grieving king,

That your courtesies are farewells,

That the key will be denied you,

The infidels’ cross eclipse the moon,

The afternoon you gaze on prove your last.

Granada, 1976.

Things That Might Have Been

I think of things that weren’t, but might have been.

The treatise on Saxon myths Bede never wrote.

The inconceivable work Dante might have had a glimpse of,

As soon as he’d corrected the Comedy’s last verse.

History without the afternoons of the Cross and the hemlock.

History without the face of Helen.

Man without the eyes that gave us the moon.

On Gettysburg’s three days, victory for the South.

The love we never shared.

The wide empire the Vikings chose not to found.

The world without the wheel or the rose.

The view John Donne held of Shakespeare.

The other horn of the Unicorn.

The fabled Irish bird that lights on two trees at once.

The child I never had.

Inferno V:129

They let fall the book, when they see

that they are the ones in the book.

(They will be in another, greater,

but what can that matter to them.)

Now they are Paolo, Francesca,

not two friends who are sharing

the savour of a fable.

They gaze with incredulous wonder.

Their hands do not touch.

They’ve discovered the sole treasure;

They have found one another.

They betray no Malatesta,

since betrayal requires a third

and they are the only two on earth.

They are Paolo and Francesca

and the queen and her lover too

and all the lovers who’ve been

since Adam went with Eve

in the Paradise garden.

A book, a dream reveals

that they are forms in a dream once

dreamt in Brittany.

Another book will ensure that men,

dreams also, dream of them.

The Just

A man who, as Voltaire wished, cultivates his garden.

He who is grateful that music exists on earth.

He who discovers an etymology with pleasure.

A pair in a Southern café, enjoying a silent game of chess.

The potter meditating on colour and form.

The typographer who set this, though perhaps not pleased.

A man and a woman reading the last triplets of a certain canto.

He who is stroking a sleeping creature.

He who justifies, or seeks to, a wrong done him.

He who is grateful for Stevenson’s existence.

He who prefers the others to be right.

These people, without knowing, are saving the world.

Shinto

When misfortune confounds us

in an instant we are saved

by the humblest actions

of memory or attention:

the taste of fruit, the taste of water,

that face returned to us in dream,

the first jasmine flowers of November,

the infinite yearning of the compass,

a book we thought forever lost,

the pulsing of a hexameter,

the little key that opens a house,

the smell of sandalwood or library,

the ancient name of a street,

Jorge Luis Borges Age

the colourations of a map,

an unforeseen etymology,

the smoothness of a filed fingernail,

the date that we were searching for,

Jorge Luis Borges Pronunciation

counting the twelve dark bell-strokes,

a sudden physical pain.

Eight million the deities of Shinto

who travel the earth, secretly.

Those modest divinities touch us,

touch us, and pass on by.

The Sum

The silent friendliness of the moon

(misquoting Virgil) accompanies you

since that one night or evening lost

in time now, on which your restless

eyes first deciphered her forever

in a garden or patio turned to dust.

Forever? I know someone, someday

will be able to tell you truthfully:

‘You’ll never see the bright moon again,

You’ve now achieved the unalterable

sum of moments granted you by fate.

Useless to open every window

in the world. Too late. You’ll not find her.’

We live discovering and forgetting

that sweet familiarity of the night.

Take a long look. It might be the last.

Elegy for a Park

The labyrinth is lost. Lost too

all those lines of eucalyptus,

the summer awnings and the vigil

of the incessant mirror, repeating

the expression of every human face,

everything fleeting. The stopped

clock, the tangled honeysuckle,

the arbour, the frivolous statues,

the other side of evening, the trills,

the mirador and the idle fountain

are things of the past. Of the past?

If there’s no beginning, no ending,

and if what awaits us is an endless

sum of white days and black nights,

we are already the past we become.

We are time, the indivisible river,

are Uxmal, Carthage and the ruined

walls of the Romans and the lost

park that these lines commemorate.

Borges and I

The other one, Borges, is the one to whom things happen. I wander through Buenos Aires, and pause, perhaps mechanically nowadays, to gaze at an entrance archway and its metal gate; I hear about Borges via the mail, and read his name on a list of professors or in some biographical dictionary. I enjoy hourglasses, maps, eighteenth century typography, etymology, the savour of coffee and Stevenson’s prose: the other shares my preferences but in a vain way that transforms them to an actor’s props. It would be an exaggeration to say that our relationship is hostile; I live, I keep on living, so that Borges can weave his literature, and that literature justifies me. It’s no pain to confess that certain of his pages are valid, but those pages can’t save me, perhaps because good writing belongs to no one, not even the other, but only to language and tradition. For the rest, I am destined to vanish, definitively, and only some aspect of me can survive in the other. Little by little, I will yield all to him, even though his perverse habit of falsifying and exaggerating is clear to me. Spinoza understood that all things want to go on being themselves; the stone eternally wishes to be stone, and the tiger a tiger. I am forced to survive as Borges, not myself (if I am a self), yet I recognise myself less in his books than in many others, less too than in the studious strumming of a guitar. Years ago I tried to free myself from him, and passed from suburban mythologies to games of time and infinity, but now those are Borges’ games and I will have to think of something new. Thus my life is a flight and I will lose all and all will belong to oblivion, or to that other.

I do not know which of us is writing this page.

Index of First Lines

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2008, 2013 All Rights Reserved

Subject to certain exceptions, this work may be freely reproduced, stored, and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

ThreeVersions of Judas*

Jorge Luis Borges

There seemed a certainty in degradation.

- T. E. Lawrence, Seven Pillars of Wisdom

In Asia Minor or in Alexandria, in the second century of our faith(when Basilides was announcing that the cosmos was a rash and malevolentimprovisation engineered by defective angels), Nils Runeberg might havedirected, with a singular intellectual passion, one of the Gnostic monasteries.Dante would have destined him, perhaps, for a fiery sepulcher; his name mighthave augmented the catalogues of heresiarchs, between Satornibus andCarpocrates; some fragment of his preaching, embellished with invective, mighthave been preserved in the apocryphal Liber adversus omnes haereses ormight have perished when the firing of a monastic library consumed the lastexample of the Syntagma. Instead, God assigned him to the twentiethcentury, and to the university city of Lund. There, in 1904, he published thefirst edition of Kristus och Judas; there, in 1909, his masterpiece Demhemlige Frälsaren appeared. (Of this last mentioned work there exists aGerman version, Der heimliche Heiland, published in 1912 by EmilSchering.)

Before undertaking an examination of the foregoing works, it isnecessary to repeat that Nils Runeberg, a member of the National EvangelicalUnion, was deeply religious. In some salon in Paris, or even in Buenos Aires, a literary person might well rediscover Runeberg's theses; but thesearguments, presented in such a setting, would seem like frivolous and idleexercises in irrelevance or blasphemy. To Runeberg they were the key with whichto decipher a central mystery of theology; they were a matter of meditation andanalysis, of historic and philologic controversy, of loftiness, of jubilation,and of terror. They justified, and destroyed, his life. Whoever peruses thisessay should know that it states only Runeberg's conclusions, not his dialecticor his proof. Someone may observe that no doubt the conclusion preceded the'proofs'. For who gives himself up to looking for proofs of somethinghe does not believe in or the predication of which he does not care about?

The first edition of Kristus och Judas bears the followingcategorical epigraph, whose meaning, some years later, Nils Runeberg himselfwould monstrously dilate:

Not one thing, but everything tradition attributes to Judas Iscariotis false.

(De Quincey, 1857.)

Preceded in his speculation by some German thinker, De Quincey opinedthat Judas had betrayed Jesus Christ in order to force him to declare hisdivinity and thus set off a vast rebellion against the yoke of Rome; Runebergoffers a metaphysical vindication. Skillfully, he begins by pointing out howsuperfluous was the act of Judas. He observes (as did Robertson) that in orderto identify a master who daily preached in the synagogue and who performedmiracles before gatherings of thousands, the treachery of an apostle is notnecessary. This, nevertheless, occurred. To suppose an error in Scripture isintolerable; no less intolerable is it to admit that there was a singlehaphazard act in the most precious drama in the history of the world. Ergo, thetreachery of Judas was not accidental; it was a predestined deed which has itsmysterious place in the economy of the Redemption. Runeberg continues: TheWord, when It was made flesh, passed from ubiquity into space, from eternityinto history, from blessedness without limit to mutation and death; in order tocorrespond to such a sacrifice it was necessary that a man, as representativeof all men, make a suitable sacrifice. Judas Iscariot was that man. Judas,alone among the apostles, intuited the secret divinity and the terrible purposeof Jesus. The Word had lowered Himself to be mortal; Judas, the disciple of theWord, could lower himself to the role of informer (the worst transgressiondishonor abides), and welcome the fire which can not be extinguished. The lowerorder is a mirror of the superior order, the forms of the earth correspond tothe forms of the heavens; the stains on the skin are a map of the incorruptibleconstellations; Judas in some way reflects Jesus. Thus the thirty pieces ofsilver and the kiss; thus deliberate self-destruction, in order to deservedamnation all the more. In this manner did Nils Runeberg elucidate the enigmaof Judas.

The theologians of all the confessions refuted him. Lars PeterEngström accused him of ignoring, or of confining to the past, the hypostaticunion of the Divine Trinity; Axel Borelius charged him with renewing the heresyof the Docetists, who denied the humanity of Jesus; the sharp tongued bishop ofLund denounced him for contradicting the third verse of chapter twenty-two ofthe Gospel of St.

Luke.

These various anathemas influenced Runeberg, who partially rewrotethe disapproved book and modified his doctrine. He abandoned the terrain oftheology to his adversaries and postulated oblique arguments of a moral order.He admitted that Jesus, 'who could count on the considerable resourceswhich Omnipotence offers,' did not need to make use of a man to redeem allmen. Later, he refuted those who affirm that we know nothing of theinexplicable traitor; we know, he said, that he was one of the apostles, one ofthose chosen to announce the Kingdom of Heaven, to cure the sick, to cleansethe leprous, to resurrect the dead, and to cast out demons (Matthew 10:7-8;Luke 9:1). A man whom the Redeemer has thus distinguished deserves from us thebest interpretations of his deeds. To impute his crime to cupidity (as somehave done, citing John 12:6) is to resign oneself to the most torpid motiveforce. Nils Runeberg proposes an opposite moving force: an extravagant and evenlimitless asceticism. The ascetic, for the greater glory of God, degrades andmortifies the flesh; Judas did the same with the spirit. He renounced honor,good, peace, the Kingdom of Heaven, as others, less heroically, renouncedpleasure.1 With a terrible lucidity he premeditated his offense.

In adultery, there is usually tenderness and self-sacrifice; inmurder, courage; in profanation and blasphemy, a certain satanic splendor.Judas elected those offenses unvisited by any virtues: abuse of confidence(John 12 :6) and informing. He labored with gigantic humility; he thoughthimself unworthy to be good. Paul has written: Whoever glorifieth himself,let him glorify himself in the Lord. (I Corinthians 1:31); Judas soughtHell because the felicity of the Lord sufficed him. He thought that happiness,like good, is a divine attribute and not to be usurped by men.2

Many have discovered post factum that in the justifiable beginningsof Runeberg lies his extravagant end and that Dem hemlige Frälsaren is a mereperversion or exacerbation of Kristus och Judas. Toward the end of 1907,Runeberg finished and revised the manuscript text; almost two years passedwithout his handing it to the printer. In October of 1909, the book appearedwith a prologue (tepid to the point of being enigmatic) by the Danish HebraistErik Erfjord and bearing this perfidious epigraph: In the world he was, andthe world was made by him, and the world knew him not (John 1:10). Thegeneral argument is not complex, even if the conclusion is monstrous. God,argues Nils Runeberg, lowered himself to be a man for the redemption of thehuman race; it is reasonable to assume that thesacrifice offered by him was perfect, not invalidated or attenuatedby any omission. To limit all that happened to the agony of one afternoon onthe cross is blasphemous.3 To affirm that he was a man and that he wasincapable of sin contains a contradiction; the attributes of impeccabilitasand of humanitas are not compatible. Kemnitz admits that the Redeemercould feel fatigue, cold, confusion, hunger and thirst; it is reasonable toadmit that he could also sin and be damned. The famous text 'He willsprout like a root in a dry soil; there is not good mien to him, nor beauty;despised of men and the least of them; a man of sorrow, and experienced inheartbreaks' (Isaiah 53:2-3) is for many people a forecast of theCrucified in the hour of his death; for some (as for instance, Hans LassenMartensen), it is a refutation of the beauty which the vulgar consensusattributes to Christ; for Runeberg, it is a precise prophecy, not of onemoment, but of all the atrocious future, in time and eternity, of the Word madeflesh. God became a man completely, a man to the point of infamy, a man to thepoint of being reprehensible - all the way to the abyss. In order to save us,He could have chosen any of the destinies which together weave the uncertainweb of history; He could have been Alexander, or Pythagoras, or Rurik, orJesus; He chose an infamous destiny: He was Judas.

In vain did the bookstores of Stockholm and Lund offer thisrevelation. The incredulous considered it, a priori, an insipid and laborioustheological game; the theologians disdained it. Runeberg intuited from thisuniversal indifference an almost miraculous confirmation. God had commandedthis indifference; God did not wish His terrible secret propagated in theworld. Runeberg understood that the hour had not yet come. He sensed ancientand divine curses converging upon him, he remembered Elijah and Moses, whocovered their faces on the mountain top so as not to see God; he rememberedIsaiah, who prostrated himself when his eyes saw That One whose glory fills theearth; Saul who was blinded on the road to Damascus; the rabbi Simon ben Azai,who saw Paradise and died; the famous soothsayer John of Viterbo, who went madwhen he was able to see the Trinity; the Midrashim, abominating the impious whopronounce the Shem Hamephorash, the secret name of God. Wasn't he, perchance,guilty of this dark crime? Might not this be the blasphemy against the Spirit,the sin which will not be pardoned (Matthew 12:3)? Valerius Soranus died forhaving revealed the occult name of Rome; what infinite punishment would be hisfor having discovered and divulged the terrible name of God?

Intoxicated with insomnia and with vertiginous dialectic, NilsRuneberg wandered through the streets of Malmö, praying aloud that he be giventhe grace to share Hell with the Redeemer.

He died of the rupture of an aneurysm, the first day of March 1912.The writers on heresy, the heresiologists, will no doubt remember him; he addedto the concept of the Son, which seemed exhausted, the complexities of calamityand evil.

up1 Borelius mockingly interrogates: Why did he not renounce torenounce? Why not renounce renouncing?

up2 Euclydes da Cunha, in a book ignored by Runeberg, notesthat for the heresiarch of Canudos, Antonio Conselheiro, virtue was 'akind of impiety almost.' An Argentine reader could recall analogouspassages in the work of Almafuerte. Runeberg published, in the symbolist sheetSju insegel, an assiduously descriptive poem, 'The Secret Water': thefirst stanzas narrate the events of one tumultuous day; the last, the findingof a glacial pool; the poet suggests that the eternalness of this silent waterchecks our useless violence, and in some way allows and absolves it. The poemconcludes in this way:

The water of the forest is still and felicitous,

And we, we can be vicious and full of pain.

up3 Maurice Abramowicz observes: 'Jesus, d'apres cescandinave, a toujours le beau role; ses deboires, grace a la science destypographes, jouissent d'une reputation polyglotte; sa residence detrente-trois ans parmis les humains ne fut, en somne, qu'unevillegiature.' Erfjord, in the third appendix to the

Christelige Dogmatik, refutes this passage. He writes that thecrucifying of God has not ceased, for anything which has happened once in timeis repeated ceaselessly through all eternity. Judas, now, continues to receivethe pieces of silver; he continues to hurl the pieces of silver in the temple;he continues to knot the hangman's noose on the field of blood. (Erfjord, tojustify this affirmation, invokes the last chapter of the first volume of theVindication of Eternity, by Jaromir Hladlk.)

Translator unknown.